One of my students, Julie, recently decided to avoid headstand. She’d just read William Broad’s book The Science of Yoga, which investigates yoga’s purported benefits. Hmm, I read that book when it was published in 2012—and I recall its numerous accounts of serious injuries. The case studies typically involved extreme behavior, however, with subjects holding poses for hours or doing strenuous maneuvers without props. The injuries seemed unlikely to affect “ordinary” practitioners. Did the book overly influence Julie?

That said, anyone can see that Salamba Sirsasana (Supported Headstand) isn’t an innate body position. Upside-down. Full weight-bearing on crown and cervical spine. Minimally propped by a wall (or nothing at all). Typically held for longer than a minute. It’s a singular, inherently tricky pose.

I’d researched headstand effects on intraocular pressure and glaucoma several years ago. It’s time for another look at Sirsasana.

Measuring Weight-Bearing Load in Headstand

For healthy practitioners, without pre-existing conditions, the main risk is cervical spinal injury. I found a relevant Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies study published in 2015 by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin. They found 45 yoga practitioners experienced in headstand and divided them into three groups based on their typical entry/exit style:

- “symmetrical extended” (two straight legs)

- “symmetrical flexed” (two bent legs)

- “asymmetrical flexed” (one leg at a time, bent)

While subjects performed headstand, they measured the force, or weight-bearing load, during three phases: entry, stability (hold), and exit.

Force on Head and Neck

Force varied depending on phase, but average load was 40 to 48 percent of body weight. Can your neck support almost half your weight?

Force was greatest during stability phase, meaning that practitioners transferred weight from arms to head. Also, force increased over time, suggesting that longer holds (and consequent fatigue) generate greater loads.

Entering with two straight legs generated lowest load. Entering one leg at a time—the kick-up technique typical of beginners—generated highest load.

Loading Rate

Loading rate refers to how rapidly body weight shifts onto target area (here, head and neck). Faster loading rates is associated with both soft-tissue and vertebral injury—therefore slow entry into headstand is safest.

No surprise, fastest (and riskiest) loading rates occurred when kicking up one leg at a time. Entering with two straight legs produced slowest rates.

Neck Alignment

Force on neck when flexed, in contrast to when in natural extension (slight arch), is most risky. Thus it’s important to maintain neutral cervical extension throughout headstand.

Entering with two straight legs maintained the most stable neutral cervical alignment, while kicking up with momentum showed temporary cervical flexion.

Center of Pressure

Side-to-side shifting occurred mostly during entry and exit, when practitioners tried to balance load between left and right. This shifting perhaps reduced maximum force on crown, but too much swaying could cause lateral (side) pressure, also possibly damaging.

Bottom line: Don’t move your head around during headstand!

Strategies for Safe Headstands

- Risk Factors, including Age

The standard contraindications for inversions include spinal conditions, glaucoma, detached retina, osteoporosis, hypertension, and possibly pregnancy. Proceed cautiously if you have a risk factor, but remember that experience makes a difference. An adept practitioner might safely do headstand during pregnancy or despite osteoporosis, for example.

Age should be considered, even for healthy practitioners, because the spine changes over time. In general, older people have less-robust spinal discs and less range of motion.

- Body Size and Proportions

Size matters in headstand. Considering 40 to 48 percent average load, the larger you are, the more force you apply to your head and neck. While larger people (and males in general) might have correspondingly larger cervical vertebrae and discs, that might not accommodate the extra weight-bearing burden.

Have you assessed your upper-arm length versus head-and-neck length? If you have long humerus bones (relative to head plus neck), you need to raise your crown (on folded blanket or towel) to compensate. Likewise, those with short humerus bones (relatively speaking) need to raise their forearms. Sounds complicated, but I know practitioners who can set up these additional props in a snap.

- Entry/Exit Technique

If possible, learn to enter and exit headstand with zero momentum. The study assumed that entering one leg at a time always involves momentum. But adept practitioners can enter slowly, sans momentum, regardless of one or two legs, bent or straight.

Those with tight hamstrings probably need to kick up with some momentum, however. In that case, arms and shoulders must work harder to stabilize the foundation.

Interestingly, in the study, those who exited headstand one leg at a time, “a quick controlled fall,” had lowest loads, while those who exited with two straight legs showed more cervical flexion—opposite of entry. So, if fatigued, those who enter with two straight legs might opt to exit more quickly, one leg at a time.

- Duration

Is longer better? There’s no rule for headstand length; practitioners must experiment and figure out an ideal duration for themselves. In my opinion, a five-minute headstand is more than enough for most people—in light of spine safety. (In the study, subjects held headstand only for five breaths!)

Several years ago, I experimented with holding headstand for longer than my usual five minutes. I’d set my watch timer for 10 minutes. Often, I’d exit at eight minutes, due not to fatigue, but to a sneaking suspicion that my neck had had enough.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m a big fan of long holds. For example, twice weekly I hold Vrksasana for 10 minutes per leg. Occasionally I hold Downward Dog for five or more minutes. In these poses I might feel my muscles burning with lactic acid, but I know I’m not injuring myself.

I recently read well-known Israeli teacher Eyal Shifroni’s blog post, “Inverted Asanas and Their Benefits.” He believes that Sirsasana must be held for longer than a few minutes—and he himself occasionally does 30-minute Sirsasana (followed by 45-minute Sarvangasana). That would be too much for my neck, but might be fine for others’. Trust your instincts.

- Frequency

As with duration, ideal frequency is an individual decision. Headstand daily might or might not be appropriate. For beginners just learning the pose, frequent prep practice is important to train strength and good form. For experienced practitioners, the pose, once second nature, is never forgotten by the body, even if not practiced for a while. That’s what I’ve found, anyway!

I initially hypothesized that frequent weight-bearing might strengthen the neck. But the study addressed, for comparison, carrying heavy loads on the head, as done in Africa and South Asia. African wood bearers were shown to have significantly greater cervical degeneration than peers who didn’t do head-carrying. So, repetitive stress on the neck could incrementally cause spinal damage.

- Experience Level

Entering headstand symmetrically, slowly, is safer than kicking up dynamically. So, whatever your experience level, assess your technique.

In general, beginners are more likely to kick up with uncontrolled momentum, often rushing in eagerness or nervousness. It’s imperative for beginners to nail down the foundation—elbow placement, hand clasp, crown location—and to practice holding prep variations (feet on chair seat) until everything is set in muscle memory.

- Non-Weight-Bearing Options

To go upside-down without loading the spine, one option is a headstander. Skull hangs in midair; shoulders bear body weight. You can also set up your own with two chairs or footstools.

Another option is kurunta, Iyengar yoga wall ropes, which you can find at some studios. Pelvis is held by a rope; spine and skull hang freely.

Instead of Sirsasana, you can also invert “halfway”: Release your head downward in poses such as Adho Mukha Svanasana, Pascimottanasana, and Prasarita Padottanasana. Alternately, focus on lower body and raise your legs upright in Viparita Karani.

Divergent Opinions on Headstand

I can see why my student Julie might be ambivalent about Sirsasana. On one hand, she might read Broad’s The Science of Yoga—or, if the book is TL;DR, his New York Times article, “How Yoga Can Wreck Your Body.” Other articles on yoga injuries, such as “Insight from Injury” in Yoga Journal, are widespread online.

On the other hand, headstand and other inversions are considered essential and therapeutic. In Iyengar yoga, Salamba Sirsasana commonly called the “king of poses”—and teachers such as Shifroni quote wide-ranging physiological benefits stated by Geeta Iyengar and other senior teachers.

I’m somewhere in between. I value headstand: Physically, it’s an all-body strengthener. It relieves usual gravitational pressure on lumbar spine and hip joints. I feel as if blood and lymph are circulating more fully throughout the body (whether true or not). Mentally, headstand forces me immediately to pay attention, as If going upside-down somehow rejiggers my mindset. But I never claim that Sirsasana can cure medical disorders or that lengthy holds are necessary.

Survival Instinct

Should you do Sirsasana? Ultimately you must decide for yourself regardless of others’ divergent claims. Consider both sides—and then listen to your body and your intuition.

My immediate reaction to the alarming anecdotes Broad’s case studies was, “Who are these people?” Does a typical yoga practitioner fall asleep in Supta Virasana? Sit in Vajrasana daily for hours on end? Repeatedly do shoulderstand without props, on bare floor, neck hyperflexed, sustaining chronic bruising?

These case studies are atypical—and these practitioners seem either obsessive or ego driven. Don’t most people know when they’re risking harm to themselves?

Well, maybe not. Observing my students, I see some with common sense and what I’ll call “survival instinct.” They adjust their yoga practice to their abilities. In contrast, I see others who always push to the max; if I give three options, they always choose the most challenging, whether or not appropriate.

The question is not whether headstand is risky, but whether headstand is risky for you.

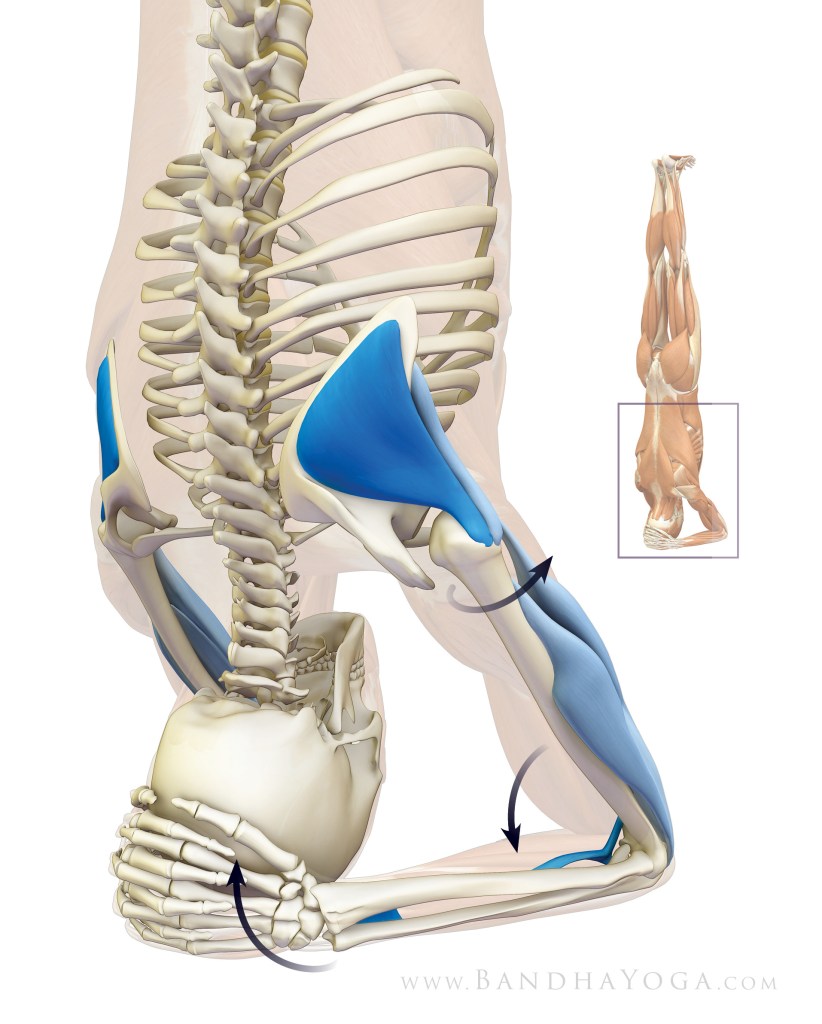

Image: Anatomy of headstand arms, Bandha Yoga, Ray Long.

Leave a Comment